Portraits of Biddy Salamander of the Broken Bay Tribe, Bulkabra Chief of Botany, Gooseberry Queen of Bungaree, as depicted by Charles Rodius in 1834 (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW - SAFE / PXA 615, Digital Order No. a1114010)

Author: Anita Heiss

Arabanoo

In December 1788, not long after the landing of the First Fleet, Governor Phillip ordered the capture of Arabanoo (born c1758). Arabanoo was dressed in European clothes, trained in English and called Manly (after his place of capture). Arabanoo became friendly with the colonists and dined regularly with Phillip, providing the first real information about Aboriginal society and culture for the Europeans. He was horrified seeing a public flogging and appalled by the decaying bodies of his people, victims of the smallpox epidemic soon after the arrival of the First Fleet. He nursed two sick children named Nabaree and Abaroo back to good health, before he fell victim himself and died in May 1789. Arabanoo was buried in the Governor’s garden, on the site of today’s Museum of Sydney.

Bennelong

Bennelong, born c1764 of the Wangal people, is one of the most notable Aboriginal people in the early history of Australia. Also known as Wolarwaree, Ogultroyee and Vogeltroya, he was one of the first to live with the settlers, to be ‘civilised’ into the European way of life and to enjoy its ‘benefits’. Bennelong (married at the time to Barangaroo) was captured with Colbee (married to Daringa) in November 1789 as part of Governor Arthur Phillip’s plan to learn the language and customs of the local people. Similarly to Arabanoo, Bennelong soon adopted European dress and ways, and learned English. Bennelong is also known to have taught George Bass the language of the Sydney Aboriginal peoples, and gave Phillip the Aboriginal name Wolawaree to locate him in a kinship relationship. This was necessary in order to communicate customs and relationship to the land.

Bennelong served the colonisers by teaching them about Aboriginal customs and language in an attempt to aid relations between the two groups. In May 1790 Bennelong was present at Manly when Phillip was speared and persuaded the governor that the attack was caused by a misunderstanding. Later that year, he asked the governor to build him a hut on what became known as Bennelong Point, the site of Sydney Opera House. Here he entertained the governor a year later.

Although he was said to have had a love-hate relationship with the settlement and Governor Phillip, Bennelong and his kinsman Yemmerrawanne travelled with the governor to England in 1792, and were presented to King George III on 24 May 1793. Yemmerrawanne died and was buried in Britain, but Bennelong returned to Sydney in February 1795, after what must have been an enormously challenging confrontation with an alien culture. He exhibited a new sense of dress and behaviour, and tried to influence his family to imitate these things. Bennelong was long troubled by the consumption of alcohol. He frequented Sydney less often and eventually died at Kissing Point on 3 January 1813.

Much of the profile of Bennelong has been created by the writings of Judge Advocate David Collins (who preferred the spelling Bennilong) and Captain Watkin Tench (who chose Bennillon). They viewed him as an experiment in ‘softening, enlightening and refining a barbarian’. While Bennelong suffered from the worst aspects of enculturation, he also represents those who tried to change the behaviour of Europeans on Aboriginal lands.

Pemulwuy

Between 1788 and 1802 Aboriginal warrior Pemulwuy lead a guerrilla war against the British settlement at Sydney Cove, and because of his resistance to the invaders, he became one of the most remembered and written about historical figures in Australian Aboriginal history. He is regarded as a courageous resistance fighter.

Pemulwuy, a Bidjigal man from the Botany Bay area, saw the damage done to Aboriginal society by the colonisers and was not tempted to befriend them as Arabanoo and Bennelong had done. He led many attacks on the settlement from Botany Bay to the Parramatta area and later to Toongabbee (Toongabbie). In 1790 he speared a much disliked convict gamekeeper by the name of John McIntyre and was then wanted for murder. In a battle in 1797 at Parramatta he was shot and hospitalised but escaped, to the delight of his community. Wanted dead or alive, Pemulwuy was finally shot dead in 1802 and his head was sent to England. His son Tedbury was taken prisoner in 1805.

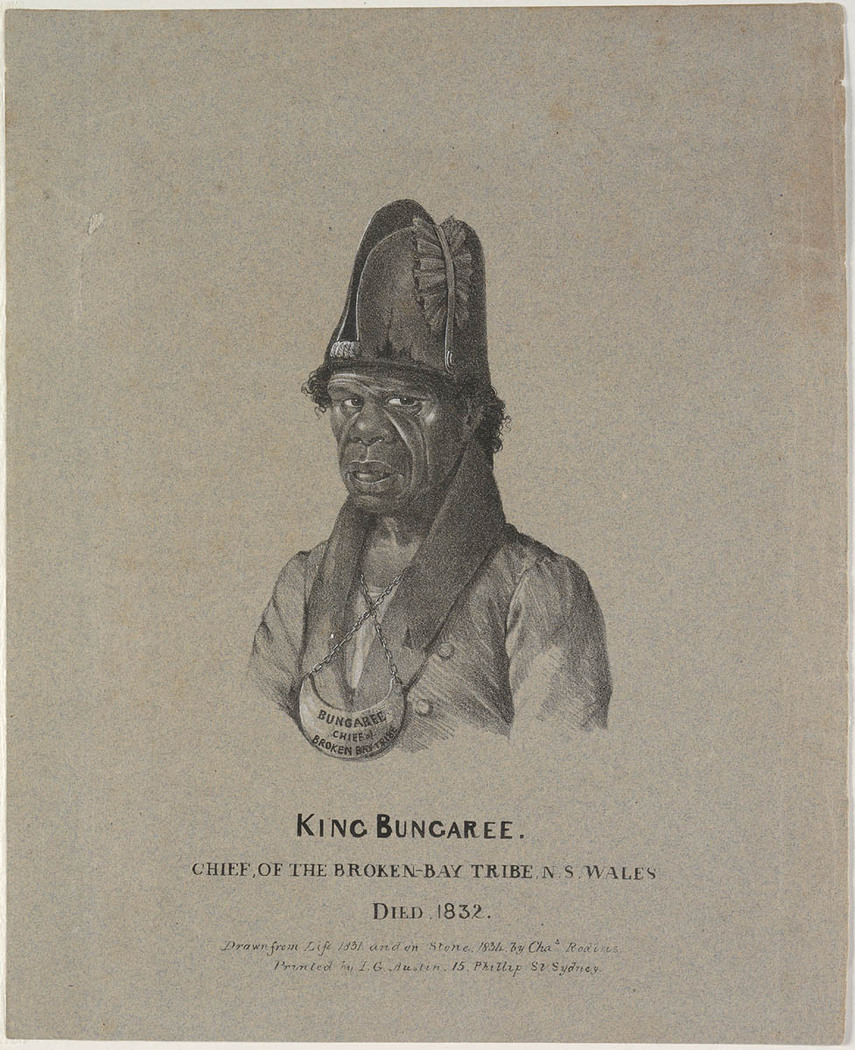

Bungaree

Known for being able to straddle both black and white societies, Bungaree (also spelt Boongaree) was from Broken Bay and moved to the Sydney area. He was known as a diplomat, mediating between his own people and the government and as an entertainer who impersonated the governors and other local figures. Bungaree was also an explorer, sailing with Matthew Flinders on his voyages around Australia, and with Phillip Parker King on the ‘Mermaid’ in 1818.

Although he often played the fool, Bungaree was an intelligent man who used his skills to get what he wanted. Governor Lachlan Macquarie, whom Bungaree befriended, built huts for him and his family twice at Georges Head opposite the entrance of Port Jackson. He was helpful to settlers by tracking escaped convicts, but was also influential within his own Aboriginal community taking part in corroborees and ritual battles. He also looked after the welfare of his family and community by selling or bartering fish.

Bungaree was one of the most discussed Aboriginal people of the early 19th century, and a favourite of early painters and sketchers. He was the first Aboriginal person to be appointed a ‘chief ‘ by Governor Macquarie and the first to have the dubious honour of receiving a metal gorget bearing his name and title. Bungaree was often referred to as ‘King of Port Jackson’, ‘King of the Blacks’, or ‘Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe’. He died in 1830.

Cora Gooseberry

Bungaree’s wife, Cora Gooseberry, was known as ‘Queen of Sydney to South Head’ or ‘Queen of Sydney and Botany’ and was a Sydney identity for 20 years after Bungaree’s death. Cora was often seen wrapped in a government issued blanket, her head covered with a scarf and a clay pipe in her mouth, sitting with her family and other Aboriginal people camped on the footpath outside the Cricketers’ Arms, a hotel on the corner of Pitt and Market streets in Sydney. She befriended the owner of the hotel Edward Borton who later owned the Sydney Arms Hotel in Castlereagh Street where he allowed Gooseberry to sleep at nights. Here she was eventually found dead at the age of 75, in July 1852. Borton paid for a gravestone and her burial in the Presbyterian section of the Devonshire Street Cemetery (also known as the Sandhills cemetery, it was on the site of Central Railway). Cora Gooseberry’s gravestone is now in the Pioneers cemetery at Botany.

Civil Rights

In terms of modern day warriors and fighters for the Aboriginal cause, there are a number of significant people that have either been born in or who came to Sydney in order to maintain the political struggles facing Aboriginal people.

These include Pearl Gibbs who was born at Botany Bay in 1901 and was an integral part of the Aboriginal struggle in Sydney in the 20th century. She was a member of the historic deputation to the Prime Minister following the ‘Day of Mourning and Protest’ in 1938, and was one of the main influences in establishing the Aboriginal Australian Fellowship in 1956. Gibbs also worked with William (Bill) Ferguson in the early days of the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA) helping to make the link between the two movements. Gibbs was the first and only female member of the NSW Welfare Board between 1954 and 1957, and died in Dubbo in 1983.

Alongside Pearl Gibbs was Jack Patten (1904-57) who was born in Cummeragunja on the Murray River, and settled at La Perouse in 1928. Unlike many Aboriginal people at the time, Patten attended high school and became an experienced trade union organiser and public speaker, speaking regularly on Aboriginal rights at the Domain on Sunday afternoons, along with other Aboriginal activists like Pearl Gibbs and Tom Foster. Patten and William Ferguson published a manifesto ‘Aborigines Claim Citizenship Rights’, organised the 1938 Day of Mourning Protest and lead an APA delegation to meet the Prime Minister.

William ‘Bill’ Ferguson (1882-1950) was born near Darlington Point in NSW and was a well-known public speaker and a founding member of the Aborigines Progressive Association in 1937. Ferguson had a trade union background with the Australian Workers’ Union, and was part of an unsuccessful deputation to Canberra in 1949 that submitted proposals for reforms in Aboriginal administration to the Chifley Labor Government. A member of the Labor Party at the time, Ferguson quit and later contested the national elections as an independent in the Lawson (Dubbo) electorate. He received 388 votes. Ferguson died within a few weeks of the election.

Following the political footsteps of those who inspired him, Charles ‘Chicka’ Dixon devoted himself to Aboriginal causes after hearing Jack Patten speak on Aboriginal rights in 1946. It wasn’t until the 1960s that Dixon began to get seriously involved in the Aboriginal movement and became a member of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI). Because of his commitment to Aboriginal issues and his role in developing and promoting Aboriginal art and culture through the Aboriginal Arts Board, Dixon was named Australian Aborigine of the Year in 1984.

A Wiradjuri woman, Colleen Shirley Smith, better known as Mum Shirl, was born on Erambie Mission in Cowra in 1921 and moved to Sydney with her family in the mid-1930s. Mum Shirl is best remembered for her work with Aboriginal people in prison and is the only woman in Australia to have been given unrestricted access to prisons in NSW. In 1971 she co-founded Australia’s first Aboriginal Medical Service in Redfern and, while she could not read or write English, she could speak 16 different Aboriginal languages. In 1979 Mum Shirl received an award for Parent of the Year, and was honoured with an Order of Australia and an Order of the British Empire. She died in 1998 and was given a State-like funeral at St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney.

Born in Queensland, Pat O’Shane became general secretary of FCAATSI in 1973, completed a law degree at the University of NSW and was admitted to the NSW Bar in 1976. She was the first Aboriginal person (and the first woman) to be a head of a government department in Australia when the NSW Government set up the Ministry for Aboriginal Affairs in 1981. O’Shane was appointed a NSW Magistrate in 1986.

Born on the Todd River in Alice Springs in 1936, Charles Perkins moved to Adelaide in 1945. Perkins was the first Aboriginal person in Australia to attend university and in 1964 completed a Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Sydney. He was described as a ‘revolutionary without a revolution’ at the age of 15 and in 1965 was a significant member of a bus load of students from Sydney University who travelled across the state of NSW on what was termed the ‘Freedom Rides’.

Sporting greats

There are a number of Sydney born and based sports people that have excelled in their chosen fields. The three Ella brothers Glen, Mark and Gary grew up in Sydney’s La Perouse and went to Matraville High School and all played Rugby Union for Randwick, NSW and Australia. Their sister Marcia Ella (OAM) represented NSW and Australia in netball and participated in the World Championships in Scotland. Born in Surry Hills, Sharon Finnan followed in the steps of Marcia Ella and played netball for both NSW and Australia.

Basketballer Claude Williams was born in Camperdown in 1952 and represented NSW for five years. He also played 12 Rugby League games for South Sydney (1972-73) and coached the Sydney Kings in 1988.

In Rugby League, Aboriginal sportsmen have excelled with Sydney-born John (Chicka) Ferguson playing for Newtown, Easts, Canberra and Wigan (UK) and Australia.

Another sporting achiever born in Sydney was Harry Williams who played Soccer for St George and Canberra City and represented Australia (including six World Cup matches) between 1970 and 1978.

Adam Schreiber made the World Junior Titles in Squash in 1986 and won the NSW Junior Open (1982-87) and South Pacific Open (1981 and 1983). Between 1986 and 1990, Schreiber was winner of five International events.

John Kinsella was Australian flyweight champion (1968, 1972 and 1975) and represented Australia at the Mexico Olympics (1968), Munich (1972) and the World Championships in Istanbul (1974).

Dave Sands was a Dhungutti man, born near Kempsey on the NSW North coast, into a family of boxers known as ‘The Fighting Sands Brothers’. He was the first Australian boxer to achieve success overseas, returning from the United Kingdom with the Middleweight Championship of the British Empire. In his short career, he simultaneously held the Australian Middleweight, Light Heavyweight and Heavyweight titles.

When in Sydney, Sands trained at Laming’s Gym at 49 Glebe Point Road (currently Gleebooks bookshop) in Glebe. His training sessions at the gym and in nearby Victoria Park attracted large crowds of admiring fans. Tragically, Sands was killed in a truck accident, near Dungog, in 1952, aged just 26. In 1998, he was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame. A plaque detailing Dave Sands’ life and achievements stands on the corner of Glebe Point Road and Parramatta Road, Glebe.

About the author

Dr Anita Heiss is from the Wiradyuri nation of central NSW, the author of over 20 books and Professor of Communications at the University of Queensland.

Further reading:

Tatz, Colin 1995, Obstacle race: Aborigines in sport, UNSW Press, Sydney, NSW, Australia