Pencil sketches for a portrait of Bungaree by Charles Rodius, 1829 (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW - SAFE / PXA 615)

Author: Anita Heiss

The ways in which Aboriginal people have been portrayed by non-Aboriginal people reflect Euro-centric values and have been largely negative. Strong representations of Aboriginal people and society have developed over time, often classifying individuals as ‘traditional Aborigines’ (those in remote areas), ‘contemporary Aborigines’ (those in regional towns or urban centres like Sydney), and at times more specifically as ‘Aboriginal activists’ (those who voice concerns about the treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people). The politics of these stereotypes and their effects on race relations in places like the city of Sydney began early in the country’s post-invasion history.

One of the earliest European artists to portray the lifestyle of the Eora was known simply as the ‘Port Jackson Painter’. His rich, sympathetic portraits became well-known visual representations of the people who once populated the area. His sketches often portrayed the ‘natives’ fishing and throwing spears with woomeras. Most of the originals of these drawings are held in the Natural History Museum in London. Some of the drawings originally attributed to Governor John Hunter are now believed to have been the work of the Port Jackson Painter, whose work has recently been attributed to a midshipman named Henry Brewer who arrived on the First Fleet. Another artist, convict Thomas Watling, was more typical of his time, portraying the local people in derogatory and negative ways.

Later artists of the 1830s such as Augustus Earle, Charles Rodius and William H Fernybough focused more on portraits of individual people like Bungaree and Cora Gooseberry. Often Aboriginal people were portrayed allegorically, as symbols of a primitive state, with Sydney Town representing ‘civilisation’ taming a wild land.

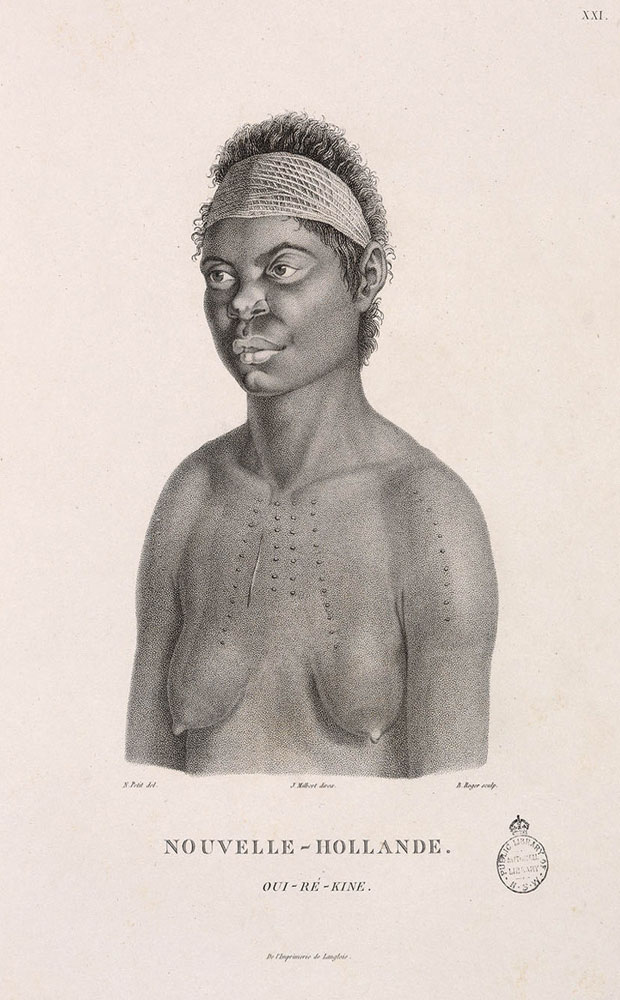

By the 1890s, Sydney’s commercial photographers such as Henry King and Charles Kerry regarded Aboriginal people as interesting subjects, but the standards applied were not the same as those for white people. Charles Kerry’s advertisements for his studio at 310 George Street included a bare-breasted Aboriginal woman titled ‘A Princess Royal’. This sort of portrayal of Aboriginal women reflected two attitudes to black women; one of them being exotic, but the other accepting a double standard on the subject of nudity.

Some of Charles Kerry’s studio shots had Aboriginal women posed suggestively with animal skins draped across their bodies. The ‘female noble savage’ was to appear sexually innocent, yet display the promise of exotic performance. Such nude shots of Aboriginal women showed the different conventions applying to them and to European women, for similar photos of white women would have been considered pornographic and socially unacceptable.

Aboriginal models in Kerry’s photographs depicted a generic race, rather than portraying people from particular regions and nations with distinct cultures. The titles and poses of Kerry’s subjects were generalised, with captions like ‘Aborigines Kindling a Fire’, ‘Aborigines Camp’, ‘Group of Girls in European Dress’, ‘A Corroboree’, ‘An Aboriginal Fight’, and ‘Aboriginal with Hunting Weapons’. And many studio photos done in Sydney claimed to be of Aboriginal warriors (‘Mary River Warrior’), princes (‘Prince of Wales Island Native’) and natives (‘Gilbert River Native’) allegedly from faraway places. Some of Kerry’s studio shots use a tropical island backdrop, reminiscent of somewhere in the Pacific. Such photographs were very popular, and many were reprinted several times. A catalogue of 12 post cards of these images was produced as a souvenir series called the ‘Travelling Salesman’.

Aboriginal people were often represented as mysterious and intriguing by white people in positions of power. They saw Aboriginal women as objects, and treated them differently to Aboriginal men, viewing them as ‘feminine delicacy’. Such views of Aboriginal women often reflected more about the European men themselves, than their chosen subjects. The creation of such female images also shows the destructive nature of colonisation when European art, made for a European audience, perpetuated denigrating attitudes to Aboriginal women.

Other 19th century images of Aboriginal people have the ‘noble savage’ male as strong, protective and active while the young female sits submissively inside the hut, cradling her infant. The Aboriginal men in Kerry’s photographs were often posed in positions of hunting, throwing boomerangs or fighting. Just as they were often portrayed in colonial writing in a negative manner in order to justify colonisation, so images of savage Aboriginal men displaying brutality towards women and children helped to justify their subjugation by the colonial powers.

About the author

Dr Anita Heiss is from the Wiradyuri nation of central NSW, the author of over 20 books and Professor of Communications at the University of Queensland.

Further reading

Jane Lydon (ed.) 2014, Calling the shots: aboriginal photographies, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, ACT

Nicole Peduzz 2011, Travelling Minuatures: Kerry & Co’s Postcards of the Pacific (1893–1917), unpublished PhD University of East Anglia